|

I, Robot

Cast: Will Smith, Bridget Moynahan, Bruce Greenwood, James Cromwell, Chi McBride, Alan Tudyk.

Directed by Alex Proyas.

Written by Jeff Vintar and Akiva Goldsman.

Suggested by Isaac Asmov's book.

Produced by Laurence Mark, John Davis, Topher Dow, and Wyck Godfrey.

Distributed by 20th Century Fox.

114 minutes.

"I, Robot" is a re-hash/re-mix/stirred in concoction of "AI: Artificial Intelligence" added to a sprinking

of Philip K. Dick movies, a freshly microwaved mix of Blade Runner and Minority Report topped with a big dollop of cheese.

For although it is, as the movie's credits frankly state, "suggested by Isaac Asimov's book," it clearly wants to

model itself after the filmed tales of the other science fiction author, whose works seem so blissfully wedded to Hollywood's

story needs.

This is mostly evident in two aspects of the film. First, its aesthetic is largely borrowed from Minority Report - the

look is predominantly bright, with lots of white. Product placement is rampant, although here it isn't accompanied by the

smirking wink that suggests the insidious invasiveness of advertising in the future. Technology is represented mostly by metropolitan

building and transportation advancements - self-driving cars on long, streamlined roads pervade the screen. However, the film's

production design should be credited with giving the year 2035 a reasonable, halfway feel that doesn't seem too technologically

ahead for its own good. It looks the way it ought to - with new devices grafted on to old foundations. Also, the robots, both

old and new models, are a visual delight. Overall, however, the influence of Steven Spielberg's recent sci-fi films is beyond

conspicuous.

Secondly, and more significantly, this film is less about the distortion of Asimov's "Three Laws of Robotics",

which his book explored, than it is about the possibility of blatantly disregarding them. The two major characters of the

film are Detective Spooner (Will Smith) and "Sonny" (voice of Alan Tudyk), one of a particularly advanced breed

of robots with human-like faces. Spooner thinks robots are cold machines that can't be trusted, but Sonny exists as an antithesis

to his theory - a robot who has been uniquely endowed with the ability to feel "emotion." As a result, Sonny can

disobey the Three Laws with his human-like decision making, which only spells danger to Spooner. The conflict that results

comes mainly from the struggle to accept the idea that robot intelligence can understand the concepts of existence, free will,

and feelings. Not exactly the same as Asimov, this is territory more explicitly covered in Blade Runner.

So although none of this feels new, the subject is always enjoyable to explore, but for as many virtues as I, Robot possesses,

it matches each one with a brain-dead Hollywood touch. The plot is a traditional cop story, complete with an angry chief who

doesn't believe in our hero, with the inevitable ultimate cliche of taking away his badge. It's also a little too convenient

-- Spooner is able to figure out the next piece of the puzzle too easily, too many times, through vague hints and his being

reminded of something significant through the random mutterings of other people. The film tries to clumsily justify this by

reiterating the point that most of the trail was set up by someone who was counting on Spooner's every move by anticipating

his psychology, and it's funny to see the film continually bring that up to explain its plot turns.

Perhaps most jarring are its out-of-place action sequences. They are technically proficient, but their disregard for logic

screams to belong in another movie. There are parts where Matrix-like physics seem to be required in order for the heroes

to do what they do. The action is there for its own sake, and happens whether or not the sequence is even reasonable - for

example, in one scene, Spooner's car, zooming at top speed, is trapped in a tunnel between two huge vehicles, one in front

and one behind, both travelling horizontally to cover the width of the tunnel. To kill him, each vehicle deploys robots to

attack his car, an unnecessary move when the front vehicle could simply hit the brakes.

Just as improbable is a big action sequence in the end which involves about a hundred robots attacking people on super-high

catwalks. How could those people have lasted even one minute?

I really don't mind ridiculous action sequences if the rest of the film accurately portrays a world in which those sequences

might feel at home. Here, we clearly have a film in which its examination of profound themes and its need for Hollywood conventionality

are at odds with each other. Thus, the efforts feel halfhearted for both. To further undermine its own story, I, Robot is

filled with the annoying script habit of withholding information from the audience for the sake of unveiling it at points

where the movie needs a boost in emotional investment. Nowhere is this better exemplified than in the fate of one character

who is given a very touching scene in the middle of the film, perhaps its most effective one, only to have that effectiveness

entirely negated by an event which occurs close to the climax. That event is a classic case of the film's ill-advised preference

of playing down to its audience, even as it has lured in that most trustworthy of intelligent viewers - those willing to embrace

the perplexing human dilemmas in science fiction. Sadly, the big budget movie-making process has seriously diluted I, Robot's

remaining nutritional value.

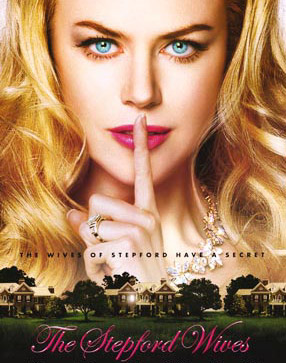

The Stepford Wives

Directed by: Frank Oz

Cast: Nicole Kidman, Matthew Broderick, Christopher Walken, Bette Midler, Glenn Close

Unfunny, uninvolving, and filled with enough phoned-in performances to make you wince, this really is one of the worst films

I have had the displeasure of enduring over the past few years.

The premise is somewhat similar to Ira Levin's original novel. Joanna (Nicole Kidman) is a high-powered TV executive who

moves with her husband (Matthew Broderick) and two children to the picture-perfect town of Stepford, Connecticut. The wives

of the town, whose perky, effervescent leader is played by Glenn Close, are all stunningly beautiful with thousand-watt smiles.

But dark secrets lurk beneath a seemingly innocent veneer, and the local men's club (comprising the husbands and led by Christopher

Walken) gives Joanna a reason to stand back and re-assess. Soon, she is drawn into a mysterious web of events that might threaten

to destroy the lives of her family, and possibly her own as well.

Let's start with the fact that Ira Levin's novel and its first cinematic adaptation were intended as a dark mystery devoid

of inconsequential levity and screwball sensibilities. Why it was recently green-lighted as a comedy I cannot begin to imagine.

The most blatant error is the film's lack of cohesiveness and involvement. The scenes feel like a series of bad sketches thrown

together to form an episodic disaster.

Depth-of-character is only hinted at, but never stretched beyond anything one-dimensional. The best example of this is

Roger Bart, who embodies the stereotypical screaming gay man. He is undoubtedly funny, but his wry, witty dialogue seems more

at home in an episode of Will & Grace or in a brief comic vignette. The only thing mildly engaging about the film is an

over abundance of one-liners that eventually becomes repetitive, irritating, and pointless; the transitions from scene to

scene are not there to further character and story, but to position us for the next lame attempts at painfully sophomoric

comedy.

Following from this, I have to say that it was not only infuriating, but insulting to see comparative talents like Glenn

Close, Matthew Broderick, Nicole Kidman, Christopher Walken, Jon Lovitz, Bette Midler (and also director Frank Oz) wasted

on drivel like this. These are not parts to which they might apply their unique talents, but are instead paper-thin roles

that could easily be filled by lesser actors.

The Stepford Wives is a chaotic mess of uninteresting characters that, when put together, are vastly inferior to the sum

of their parts. They form no coherence except for transient moments within scenes, and usually just for the purpose of a single

barrage of the aforementioned poor one-liners. The surprises and plot points are so sloppily conceived that one is forced

to just sit dazed in confusion and wonder why (and how) the hell the picture went there in the first place.

By the end of the film, I was reduced to sheer boredom. The conclusion is so inept, desultory, and just plain bad, that

I actually started hoping it would get worse so I could laugh. You know you're in trouble when actors of this calibre attempt

drama, and the result is so grim, it's funny. This is atrocious and an insult to Levin's book and the sublime original film

as directed by Bryan Forbes.

Fahrenheit 9/11

Written Produced Narrated and Directed by Michael Moore

Harriet Beecher Stowe's novel "Uncle Tom's Cabin", which enumerated the evils of slavery in shocking detail to a

nation that had all but turned a blind eye to what was known as "the peculiar institution"; is often quoted as a

catalyst for the American Civil War. In an ideal(istic) world, let's hope that Michael Moore's incendiary documentary "Fahrenheit

9/11" might be able to contribute towards a restoration of order in Iraq - and a day when there may be transparent integrity

in the American government. Both works have much in common. They are partisan, fervent, and biased in the extreme, not allowing

any other point of view than the one each expounds. In Moore's case, the direct link between the House of Saud and the Bush

dynasty.

He uses the attacks on 9/11, which (and highly effectively) we hear rather than see as the screen goes black for several

minutes, as his focal point. Looking back from them, Moore follows the money trail from the Saudis to George W.'s first failed

oil business in Midland Texas. Picking up right after the twin towers fell, he shows how the US government got all the members

of the Bin Laden family, who were in America at that time, out of the country on the same day with a minimum of passport control.

This at a time if you recall, when no flights other than military ones were allowed within US air space.

Make no mistake, Moore is extremely angry. With the sort of rage that burns white hot until it is distilled down to a

cold and very deliberate purpose. With careful and ample documentation, he draws a very clear line between the Saudi desire

for influence in the richest country in the world (USA), and the desire of the Bush family and their cronies for vast amounts

of money. As Moore puts it with his distinct brand of vitriol, if the American people are paying you $400,000 a year to be

President, and the Saudis have paid your family over a billion over the last decade or so with no signs of the payments stopping,

'Who's your Daddy?'

The answer is a war in Afghanistan - not to capture/oust/kill Osama Bin Laden (and why the delay of a full two months

before sending a ridiculously limited number of troops there?), but rather to clear the way for a natural gas pipeline across

that country. Why? For the Saudis who want a way to move the product and for the fat contracts for all your pals who run companies

like Halliburton. Where Stowe had only her fertile and fevered imagination in the form of melodramatic fiction, Moore has

the advantage of being able to use the principles involved to convict themselves with their own words. Condeleeza Rice and

Colin Powell, for example, in February of 2001 stating that Iraq is a threat, and then, with equal assurance, taking the opposite

view a year or so later. How Moore got the conference footage of representatives taking turns gloating over how much money

they were going to make rebuilding Iraq is a coup of the first order.

Ultimately, no one gets a free ride here - especially not the Republicans, whose top dog, Bush, is depicted as an airhead

plonker propped up by his father's rich friends. The sequence showing him being told that the second tower has been hit on

9/11 and then spending seven minutes just sitting there, looking like a rabbit caught in the headlights sums that up nicely,

though Moore's narration, suggesting that because there was no one there to tell him what to do, he just kept reading the

children's book aloud at the photo opportunity in Florida, is a piquant commentary. Nor the Democrats either, who rolled over

and passed a Patriot Act without reading what it did to civil liberties. Not the media which jumped on the jingoistic bandwagon

in search of ratings. Not to mention how they fell asleep at the wheel before 9/11. Just why was it that the Taliban emissary

making a visit to an oil company's headquarters in Washington before 9/11 wasn't on the front pages? And why was it never

brought up afterwards?

Moore really has done his homework on the economics relative to Iraq, such as Bush sending soldiers to die in Iraq while

cutting their pay and benefits. More information such as this would have made it an even more disturbing film, but this is

still a guy who is the modern master of political theatre. He can drive home a point with such deadly precision, that the

opposition is left blindsided and speechless. He uses this talent to make us laugh, reading the Patriot Act aloud through

the PA system of an ice cream van, jingle playing, as it circles the Capitol Dome outside the Whitehouse. He makes us think

by cornering members of Congress and asking them to have their kids enlist for the military and go to Iraq. The way one of

those cornered congressmen looks at Moore as though he's lost his mind says it all. Then he breaks your heart while making

the blood in it boil by showing us the father of a soldier killed in Iraq asking what the kid died for, and then abruptly

cutting to a PR speech by the Chief Executive of Halliburton.

Even without all the controversy of Disney trying to squash the film's distribution in America, even without the Palme

D'Or at Cannes, this would still be a film that is impossible to ignore or to dismiss. If only a fraction of Moore's charges

is true about Bush's actions and motives for them at home and abroad, then the USA has nothing less than a criminal in office.

At the very least, this muckraker par excellence has delivered a broadsheet that should encite rioting in the streets.

He concludes with an extended quote from George Orwell on victory not being the point of war, but rather using war to

keep the social hierarchy in place. It takes on a tone far more ominous than even Orwell could ever have imagined.

Twisted

Jessica Shepard: Ashley Judd

John Mills: Samuel L. Jackson

Mike Delmarco: Andy Garcia

Dr. Melvin Frank: David Strathairn

Lieutenant Tong: Russell Wong

Lisa: Camryn Manheim

Jimmy Schmidt: Mark Pellegrino

Dale Becker: Titus Welliver

Ray Porter: D.W. Moffett

Wilson Jefferson: Richard T. Jones

Edmund Culter: Leland Orser

Directed by Philip Kaufman

Written by Sarah Thorp

Running time: 96 minutes

Seals act as silent witnesses to a series of grisly murders in Philip Kaufman's "Twisted". Why they perform such

a role is anyone's guess, but there they are, leisurely sunbathing in the San Francisco Bay, looking as sleepy and bored as

I felt while enduring this pathetic serial killer thriller. Ashley Judd is homicide investigator Jessica Sheppard, a tough

go-getter who doesn't play by the rules at work (she likes to kick misogynistic fellow officers in the groin - good on her)

or at play, which consists of habitually picking up random punters in sleazy pubs. Jessica drinks lots of wine to mask the

pain caused by her father's murderous past, but regularly getting tipsy proves problematic when her former one-night-stands

begin showing up dead.

Images of fog enveloping the Golden Gate Bridge foreshadow Jessica's escalating inability to figure out if she's responsible

for the killings, but Kaufman's ham-fisted direction makes every meaningful clue stand out in stark pop-up book fashion. The

red wine! The photo of her dead dad! The A-list actor (Big Sammy) who mysteriously disappears from the film for 30 minutes

so we can forget he might have anything to do with the crimes! Sarah Thorp's script, filled with subplots that magically disappear

when they're no longer convenient and narrative misdirections that wouldn't fool a seal, is twisted in all the wrong ways.

Although it's fleetingly suggested that Judd's voracious carnal appetites might be related to her volatile temper, Twisted

- unlike Clint Eastwood's similar (but far superior) Tightrope - is too afraid to intimately probe the sticky relationship

between sex and violence, and entirely drops the issue once the list of suspects has been narrowed down to two.

Ensnared in a film determined to play it safe, Judd, Andy Garcia (as Jessica's partner), and - apparently because Morgan

Freeman was busy - Samuel L. Jackson (as the police commissioner and Jessica's surrogate father) all go through the police

procedure motions with unremarkable competence. Their lacklustre performances are largely upstaged by those watchful seals,

whose piercing plaintive wails during the opening credits, one begins to imagine, convey despair over being forced to participate

in such a tediously routine suspense film for no discernable reason at all.

|