|

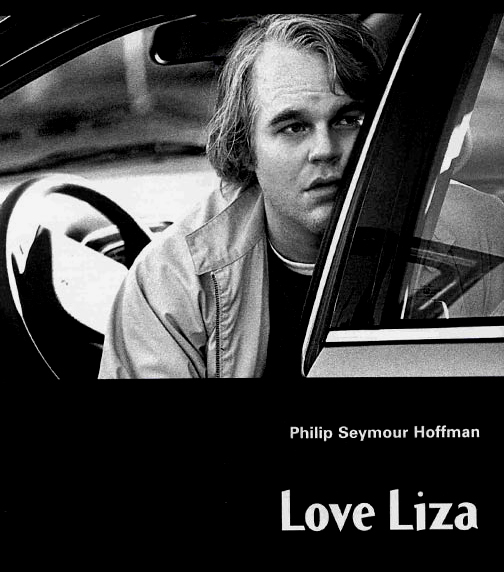

Love Liza

Producer: Ruth Charny, Chris Hanley, Jeff Roda and Fernando Sulichin

Director: Todd Louiso

Writer: Gordy Hoffman

Studio: Sony Pictures Classics

Starring:

Philip Seymour Hoffman

Kathy Bates

Jack Kehler

Grief and gasoline are the essential elements in Todd Louiso's debut feature, a heartfelt misfire about a man traumatised

by the suicide of his wife. Dumpy, scruffy Wilson Joel (Philip Seymour Hoffman) is a computer geek whose devastation following

the sudden, unexplained death of his beloved Liza puts him into a psychological downward spiral that costs him his job as

a website designer. Even his sympathetic mother-in-law Mary Ann (Kathy Bates) proves unable to help.

In his descent Wilson falls into two related obsessions. One is remote-controlled model aeroplanes, an interest which

takes hold of him when he goes off on an aimless journey that eventually links him up with Denny (Jack Kehler), an oddball

neighbour who's also an enthusiast. The other is - believe it or not - an addiction to sniffing petrol (USA: gas), which ultimately

consumes him, destroys any chance for him to retrieve his career and undermines his relationship with Mary Ann.

A further source of strain is the fact that Wilson has found a sealed suicide note from Liza which, to her mother's distress,

he's unable to open. The dramatic assumption is that learning its contents will finally give him catharsis and sort him out.

The script by Gordy Hoffman, the star's brother, is not so much a narrative as an episodic character study. The strength of

this approach is that the picture is unpredictable; the choices Wilson makes are so wonky that it's impossible to foresee

the twists. The weakness, on the other hand, is that the psychological journey he takes seems arbitrary and almost perversely

quirky. Individual moments are certainly fascinating, and the overall effect isn't without interest, but as a whole the piece

comes across as rather precious and haphazard. One element of it, however, is totally extraordinary, and that's Hoffman's

amazing performance. He's always been a superlative actor, but he really outdoes himself here, drawing an astonishingly convincing

portrait of a man at the absolute end of his emotional rope. What the script leaves largely unspoken, he creates virtually

from scratch, expressing a level of despair so complete and so persuasive that it's impossible to take your eyes off him;

it's a totally fearless turn in which Hoffman exposes himself so fully - both emotionally and physically - that the result

is wrenching. None of the other cast members approach him.

Bates is sound, but except for a single instance in which her anger at the loss of her daughter suddenly flares, her work

is more solid than imaginative. Kehler's eccentricity seems too broad, and Stephen Tobolowsky is overly unctuous as a prospective

employer who's curiously supportive of Wilson. On the technical side, "Love Liza" is adequate, though the gritty

appearance of Lisa Rinzler's cinematography gets somewhat tiresome and the depiction of Wilson's more fanciful flights is

a trifle pedestrian. In the final analysis the film offers a journey that's too random and inconclusive to be compelling,

but which Hoffman's brilliance almost makes worth taking.

_________________________________________________

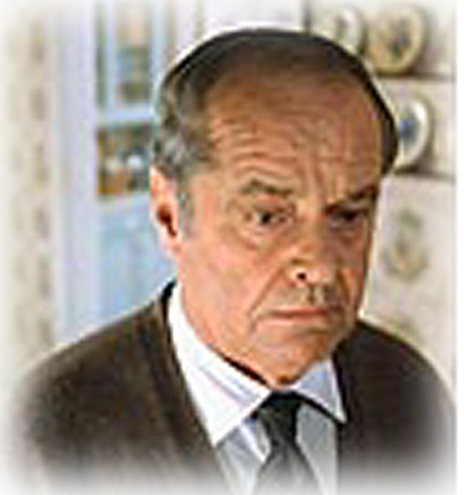

About Schmidt

Director: Alexander Payne

Cast: Jack Nicholson, Kathy Bates

With the number of critics praising About Schmidt and the seemingly universal buzz about Jack Nicholson's performance,

I was almost prepared to see a second coming of King Lear with a satirical touch by Alexander Payne.

The tongue-in-cheek writer/director created one of the top comedies of the nineties in Election, but About Schmidt ranks

as one of the flattest narratives in recent memory, and the most overrated movie of 2002. Instead of falling all over themselves

to nominate Nicholson's glib and understated performance, the Academy would be better off serving a Lifetime Achievement award.

Virtually sleepwalking through his dimwitted Everyman caricature, Nicholson is capable of so much more - years from now first

time viewers will wonder what was so remarkable about this forgettable film.

Payne's satires require the audience to see themselves as somehow superior to the cretins in his cinematic universe, and

this time that requires poking fun at the average Joes who slowly trudge through the working man's treadmill routine - home

to work, using the television remote control, eating bland home-cooked dinners, and falling asleep next to a wife who also

has established her routines.

When 66-year old Warren Schmidt (Nicholson) retires from an Omaha, Nebraska insurance company, he finds his lifetime dedication

to the company is quickly forgotten and meaningless. Without a job to go to, Schmidt practices more channel surfing and observes

his nagging wife Helen (June Squibb) more closely. "Who is this old woman who is in my house?

Helen could say much the same thing about the stranger now uneasily free to spend his golden years doing whatever he wants.

He's clearly never planned for active retirement, and Warren continues to meander purposelessly until he is struck by one

of those ubiquitous TV ads soliciting for sponsorships to Third World countries where you can feed a child for a mere $22

a month. He sends off a cheque, ends up adopting a six-year old Tanzanian boy named Ndugu, and writing the illiterate boy

letters that serve as his inner monologues.

Payne uses these letters to Ndugu as convenient voice-over devices throughout for satirical value and as a cheap sentimental

send off - a helluva lot easier to do than devise scenes to show Schmidt's inner character.

When his wife dies suddenly, Schmidt finally takes off in his Winnebago on a voyage of self-discovery. Initially intending

to visit his soon-to-be married daughter, Jeannie (Hope Davis), he first revisits places from his past and travels to others

he's always wanted to see. Of course, he discovers that the past is often obliterated, but finds arrowhead exhibits, highway

bridges, and tacky pioneering exhibits interesting (an obvious satirical slap at low brow American tourists who take side

trips to see such attractions as the world's largest ball of twine).

When an equally clueless woman self-evidently observes that Schmidt is a "sad man," Payne uses it more for a

comic moment than any epiphany. Schmidt may have more intentions of seeking happiness, hoping for a better life for his daughter,

and observing the banality of others, but he remains fundamentally unchanged, a tedious one-note acting performance that had

me wondering why I hadn't followed gut instincts in the first half hour and walked out of the cinema.

Had Payne failed to include Kathy Bates' contrasting character, the last hour would have been superfluous. Most of the

pleasures from the film lie with her supporting role as a free-spirited middle-aged divorcee who retains her sexual passion

and can curse up a storm. Still I could have done without Bates' baring it all for the hot bath scene - not that everyone

appearing in movies needs to have a beautiful body, but here it seems that Payne is again going for a cheap laugh instead

of getting inside her character.

And that's the main problem with the whole film. It's little more than a lightweight satire about the average life of

a typical Midwesterner that shows no affection for its characters like Fargo does. After one scene the joke is understood,

and it's time to move on, but Payne subjects us to a full two-hour acting performance where Jack Nicholson is obviously acting.

Not his fault - the screenwriting doesn't give his character much room to show the internal aspects.

Many will praise Nicholson for personifying a different, subdued character, rather than his usual more energetic roles,

but don't believe them. Nicholson is good enough to play this shallow cardboard character without 25+ takes to wear him down,

but it's a one-note routine that likely has Jack winking and smiling wickedly in amazement that the critics have been duped

by such a simplistic skit. A comedy about such an Everyman character need not have the poignancy and depth of Death of a Salesman,

but it should work harder to make that character multi-layered and endearing. At best About Schmidt is a forgettable mediocre

comedy. The shockingly high marks it's getting is most frightening because this will only encourage more clones of the same

nature, and there's far too much latent talent available to settle for exercises in lazy screenwriting.

__________________________________________

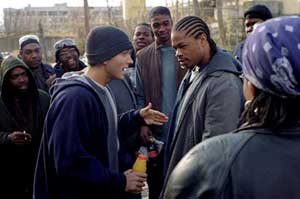

8 Mile

Starring Eminem, Kim Basinger, Brittany Murphy, Mekhi Phifer.

Directed by Curtis Hanson.

Written by Scott Silver.

Distributed by Universal Pictures.

111 minutes.

To re-quote: "There are really only seven stories in the world, and every new story you hear is a variation of one

of these seven." I think of this whenever I wonder what the point of going to see a film is, especially one like 8 Mile.

If every story has already been told before in some fashion, then a movie's value is surely not solely attributed to its story.

If that's the case, then what is its value? If we take something - a typical romantic comedy, as an example, the best

answer may be that it offers a familiar tale to comfort its audience in a non-threatening way. And since each new generation

is composed of a new audience, this comfort-story needs to be re-told for the sake of assurance. The worst answer would be

that it has no actual artistic value - that it is disposable because the film will surely be made again with the next up-and-coming

actor/actress, with little to make it significantly distinguishable.

Can we be as cynical about 8 Mile? No surprises await us in the story of a young man struggling to live life while trying

to maintain a livelihood within a harsh and uncaring world. But this is where the unique format of the motion picture shows

how valuable it can be. For what else can be used to so vividly capture the most important element in a story like this -

its cultural setting? Surely, this is one of the more ephemeral entities in the history of any country; and, thankfully, some

of these elements have been documented on film, allowing us to be able to attach colour and personality to the eras of the

past.

The movie I thought most about while watching 8 Mile was Saturday Night Fever, mainly because I happened to watch it again

on video a week earlier. There, John Travolta played a young man, not easily likeable, who slowly realizes how empty his lifestyle

is. Meanwhile, he indulges in a passion that he has a strong talent for. This could easily be the story of any male youth

from any generation. What makes Saturday Night Fever unique is how it re-creates the disco scene. Thanks to Saturday Night

Fever, I was transported back to a cultural phenomenon period just before I started dj-ing - to catch Travolta and company

burning up that cheesily lit dancefloor! The identifiable angst of his character added weight to the setting - his story

is familiar and so his world was made more real to me.

Transplant this idea to the underground hip-hop world of 1995 Detroit and we have 8 Mile. Eminem, the controversial real-life

rapper in his acting debut, stars as his own version of the troubled young man with personality flaws, facing a go-nowhere

dilemma while maintaining his sanity with his personal passion - rhyming. It's a rather serious business - young rhymers test

their mettle by participating in "battles," on the surface a put-down contest where two participants take turns

verbally slicing each other, but at heart a tense showcase for the abilities to think on one's feet, construct rhythms and

wordplay, and arouse the cheers and sympathies of an audience. It's a fascinating, if not relatively marginalized, pastime,

one which sees its power diminished by the music industry through which it gains its explosure - improvisation is, after all,

almost totally lost on a record.

Leave it to a film to help reconstruct the scenario and the atmosphere, placing the sub-cultural phenomenon in a context

we can easily step in to. The story of the struggling young man must still be there, and all Eminem is required to do is to

make it believable. He does so convincingly - director Curtis Hanson wisely exploits Eminem's natural charisma and glaring

intensity in place of exploring what range he may or may not have. We follow his character as he deals with friends, family,

job, and reputation. His hope for that ticket out of his dead-end situation rests on his chances of securing an opportunity

to record a rap demo he is currently writing. Hanson and his cast and crew compentently create a believable slice of life,

but the real appeal of the film lies in the moments when Enimem and fellow rhymers show how skillfully they can appropriate

the music and rhythm of any recorded piece and turn it in to a base for improvisational wordplay. They make as easy use of

Lynard Skynyrd's "Sweet Home Alabama" as they do of a generic drumbeat loop (ironically, 8 Mile makes far better

use of the song "Sweet Home Alabama" than the recent duff movie of the same name did). 8 Mile's finale is especially

rousing, one of this year's strongest showstoppers.

Movies like 8 Mile will always have a place as a story worth telling. It's a story that will never go away, an eternal

reflection of youth throughout multiple generations, for each new life is surely spent learning what others who have gone

before have already learned. But for each new era, that reflection shows us the different exciting ways in which the youth

could vent frustrations with displays of artistry, skill, talent and determination. As long as young people find new ways

to lose themselves while finding themselves, the movies will be there to showcase their stories.

__________________________________________

Irreversible

Directed by Gaspar Noé

Writing credits Gaspar Noé

Plot Outline: When a woman is raped by a stranger, her friend and ex-husband decide to take justice into their own hands.

Cast:

Monica Bellucci .... Alex

Vincent Cassel .... Marcus

Albert Dupontel .... Pierre

Philippe Nahon (I) .... Philippe

Jo Prestia .... Le Tenia

Stéphane Drouot .... Stéphane

Jean-Louis Costes .... Man beaten to death in club

Mourad Khima .... Mourad

Gaspar Noé .... Cameo

Running time: 95 min

Country: France

Certification: UK 18

This film features an extremely explicit and nauseating rape scene, a grotesquely ugly and revolting head-splitting-scene,

and a huge amount of arthouse pretentiousness.

Voilà "Irréversible", a movie with the ability to shock you three times: In the amazingly raw head splicing

scene, in the equally raw anal rape scene - and in all the total emptiness in between.

This is no more than an pseudo-shocker. All the messages Noé wants to bring across are lost on the exhausting way to the

boring ending. Man is an animal? Wow, how insightful. Plus it's not even brought across convincingly.

There would be so much to deconstruct in this nihilist rubbish, but I won't waste too much energy. Some filmgoers may

find that there is a slight technical interest in the film... there is indeed a rawness, and you may be fascinated by the

length of the scenes (for example the one-take-rape - although it's really tough and extremely heavy going) - but the showing-off

amounts to a big nothing.

It's an empty film and total exploitation. A dishonest, actually uptight film for intellectual revenge freaks - it fails

miserably on just about every level.

|

|

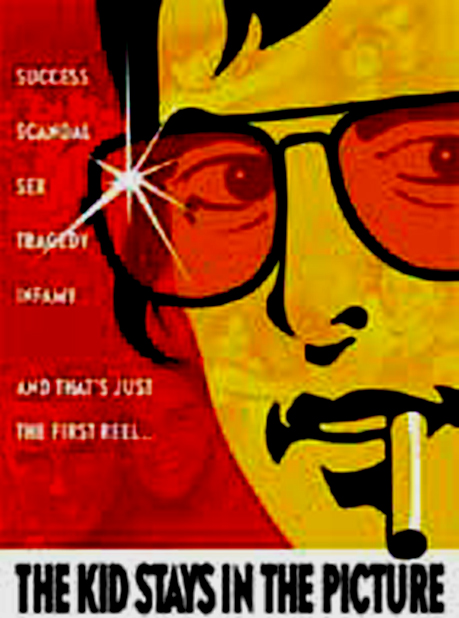

The Kid Stays In The Picture

Directed by Brett Morgen, Nanette Burstein

This is the man who told Roman Polanski, after delays in filming Rosemary's Baby, "Pick up the pace or we'll both

end up back in Warsaw."

This is the same guy who, when Henry Kissinger said he couldn't attend the premiere of "The Godfather" because

he had a military breakfast meeting the next day about the bombing of Cambodia, replied: "Maybe you didn't hear me the

first time, Henry. I said I needed you this evening."

Or, to Ali MacGraw when she said she couldn't go out with him because she was about to be married: "Planning is for

the poor. If anything is wrong between you and Blondie between now and post time, take my number - I'm seven digits away."

If you follow this film closely, you have already figured out that the speaker can only be Robert Evans.

Evans, now 71 years old, produced an astonishing number of seminal American movies while running the Paramount studios.

The Godfather is the one most people associate him with, followed closely by Love Story and Rosemary's Baby. But how about

The Odd Couple, True Grit, Serpico, Chinatown and Marathon Man?

One of the most revealing things that emerges in Brett Morgen and Nanette Burstein's inventive bio-documentary is that

half the time Evans didn't understand the scripts he approved, and the other half he was baffled by the directors he hired.

He read Chinatown and didn't have a clue what it was about. He found Roman Polanski's early films weird.

But he trusted his instinct, that groping half-aware feeling that this writer or actor or director had something new to

offer. When Francis Coppola said he wanted The Godfather to be a critique of capitalism rather than a gangster movie, Evans's

first reaction was: 'Fuck him and the horse he rode in on.' But within days he hired Coppola because his gut instinct told

him that a mafia film that wasn't going to be a gangster film would probably be a kind of movie nobody had seen before - and

of course he was right.

This film was inspired by Evans's 1994 autobiography, also called "The Kid Stays in the Picture". Evans agreed

to do the voice-over with his unmistakeably corny tough-guy persona, which is one of the film's charms. But he refused to

appear on camera, which somewhat tied the producers' hands. So did the limited archival footage of the events of Evans's checkered

career, most of which occurred behind closed doors.

The filmmakers found stylish solutions, such as the moment around 1960 when Evans, a handsome but hopeless young film

actor whose roles were getting worse ('Beware of the Kooky Killer' anyone?!), decided to make the improbable leap to producing.

The only archive material from the time was a photo of him slumping in a taxi..

Working with the photo, the special-effects people inserted a moving streetscape in the window of the cab, creating an

arresting visual with the obviously still image of Evans in the foreground.

Later on, they use a related device with some old snapshots of Evans having lunch with MacGraw on their honeymoon. Editors

scissored the lovers' images out of the photos and pasted them onto a forest backdrop, giving the pictures a cartoon-like

feel, and then showed them in sequence as a primitive animation.

These tricks, borrowed from conceptual art, somehow enhance the improbable, larger-than-life feel of Evans's story. He

was a bridging figure between the old studio system - his inspiration was the charming and dictatorial Darryl F. Zanuck -

and the corporate conglomerates that took over the movie business by the 1980s.

Evans himself, born to a wealthy family, stunningly handsome, and possessing a perfect self-confidence that seduced men

and women alike, intended to continue the studio tradition of making whatever movies he felt like. But Paramount was owned

by Gulf & Western, and its powerful board (which he called "16 of America's greatest non-smilers") could not

understand or tolerate a character like Evans. When scandal-mongering journalists falsely implicated him in the murder of

an associate, G & W seized the opportunity to boot him out. As Morgen observes, today's corporate Hollywood simply can

not make movies like Godfather and Chinatown because corporations do not understand people like Evans.

Morgen and Burstein do. Their film is a lively combative dialogue with its subject. While Evans's voice is telling us

that his reputation as a womanizer was exaggerated, the producers flash a dizzying montage of photos of him with dozens of

starlets, some of them more or less naked.

But they are not out to destroy the guy. They like him, and they want to understand him. One of the film's cleverest devices

comes from their insight that his home of 30 years, a mansion called Woodlands, was more meaningful to him than his brief

relationships with women: so they put a theatrical curtain in the garden of Woodlands, and dramatically pull it open while

telling us that walking through the house will be like walking through Evans's mind.

The best thing the film does is to show us not only what that mind looks like, but how the creative process itself operates:

messily, erratically, outside of most people's morality, but with a force and purpose that makes the machinations of the rest

of us look weak and dithery by comparison.

The Pianist

Roman Polanski's parents left Paris to return to their native Poland in 1937. When World War II broke out two years later,

6-year-old Roman was forced to watch the atrocities brought upon the Polish Jews by Nazi forces as part of their Final Solution.

He was forced to move to the Warsaw ghetto as his parents were carted off to separate concentration camps (his mother would

die, his father would survive), and, after escaping the ghetto by finding a hole in the barbwire fence, he ran around the

Polish countryside and hid with gentile families compassionate to the Jewish plight.

What is important to note about Polanski's life during the war is that he was unable to do anything himself. Impotent

by age and size, he could only watch in fear as the rest of the Krakow ghetto was obliterated by the Nazi forces. Part of

the pain and anguish that hit people so hard while watching Schindler's List was Oskar Schindler tearfully thinking about

the people that he didn't save because he kept a piece of jewellery or a car. This is a feeling that strikes many people,

especially those who were alive at the time: why is it that we essentially did nothing to stop the Nazis from continuing the

Holocaust as long as they did. It doesn't matter how many museums we build, it is a guilt that will hang over the allegedly

civilised world for generations.

Almost a decade later, Schindler's List remains the film that people will compare any Holocaust film to. Its powerful

treatment of the atrocities of Social Darwinism is, by most accounts, the best yet (not including the paramount but rarely

seen documentaries Shoah and Night and Fog) because it struck the same nerve that has been brewing in the collective Westerner

since the smoke of war moved away and exposed the terrifying enormity of the Holocaust. Most films on the subject since, from

Life is Beautiful to Jakob the Liar to The Grey Zone - have felt oddly exploitative with their look at the Holocaust as comedy,

demagoguery, and drudgery. They, from directors Roberto Benigni, Peter Kassovitz, and Tim Blake Nelson, felt far more detached

from the proceedings - the films were more like graphic history lessons than reality.

Polanski may never step foot in a concentration camp in The Pianist, his first (and probably only) foray into the Polish

treatment during World War II, because he accepts the very autobiographical feeling that a film of such weight needs (to this

point, I find it a minor miracle that Steven Spielberg was able to pull off Schindler's List, and become further impressed

by Martin Scorsese in turning down the film because he hadn't the understanding of the Holocaust that a Jewish director would

have). But Polanski ably shows that some of the most terrifying visuals came from outside the camps - I will be haunted for

some time to come by a single image in "The Pianist" of Nazis throwing a wheelchair-bound old man over a balcony

because he did not stand upon their entrance.

Like Polanski, Polish concert pianist Wladyslaw Szpilman escaped before being carted off to the camps. Instead, he was

forced to attempt survival during the Nazi takeover of Warsaw from the sidelines, which were sometimes just as violent as

the camps and battlefields.

Szpilman (Brody) is introduced with his family living in a modest Warsaw home during the outbreak of the war. He is happy

with his life, spending most of his days performing the piano for the local radio station until it is bombed by the Nazis

during one of his performances. It is with some retrospective pain to watch the Szpilmans celebrate when they learn over the

radio that England and France had entered the war to save Poland from Germany - they, like everyone else in the world, had

no idea of the long war ahead of them.

A bit of luck pulled Wladyslaw out of the line to go to the trains for Treblinka, but his family did not follow - they

all perished in the camp. Wladyslaw tried to survive in the Jewish workforce the Nazis had created, but soon found even that

was headed towards certain death. Instead, he began using a series of tangential connections to sympathetic people around

Warsaw to get him places to hide until the war might end. With every hiding place, though, came even more chances of discovery

because of the extremity of the German soldiers as their war looked more and more unwinnable.

Polanski treats Szpilman's story with such love that it is impossible to not feel his empathy with the character. In many

ways, Polanski sees himself in the man: a person left to hide during the war and watch the atrocities around him without any

ability to stop it. Most of Szpilman's hiding places had direct views of the streets that Nazis walked every day, killing

off anonymous Jews simply because they wore a star on their arms. From his perch, he watched Nazi raids of homes, the medial

aid of the fallen soldiers, and the Polish uprising that killed much of what was left of the Jewish population in Warsaw.

In the last case, you can sense in the eyes of actor Adrien Brody how much he wished that he was down there with the other

insurgents.

Brody gives a terrific, understated performance that relies mainly on his reactions to the world around him. He lost weight

and took on a gaunt physique to show the product of starvation and solitude. It is an amazing work that shows the actor's

range beyond anything he has been allowed before now. Paired with the stark production design of Allan Starski, Brody seems

like the only man who survived much of the war as he walks between the gutted buildings. The sad realisation is that at this

point there's still many more months left of warfare on the Eastern front.

The actor also learned how to play the piano for the film, which may not be such a grand achievement had he not learned

how to play it so well. While there was some use of a hand model in many of the performance scenes, much of it is Brody's

work as proven by Polanski's willingness to move the camera up to show the man connected to the rapidly moving fingers.

It was important that Brody get this ability down because music serves as an intensely important motif throughout the

film. In one of the apartment hideaways, Szpilman lives next door to a musician and is allowed to listen to the performances

every night. It is his chance to relive his once illustrious life before the war - all he has to do is close his eyes. The

next hiding place leaves him in a room with a piano, one that he cannot touch lest he let the neighbours know of his presence

(as the film makes clear, even with the support that he gets, many of the Polish people were as anti-Semitic as the Germans).

For nearly 90 minutes, we have seen Szpilman in anguish and pain - for the first time, as he gently plays a piece in his head

while moving his hands slightly above the keys, his happiness is at once revived. You want to close your eyes with him and

imagine that none of this has really happened. But you can't.

|