|

In Il Gattopardo and LÉtranger Visconti worked close to respected literary texts. In Death in Venice he follows Mann's schema

so faithfully at times that one inevitably attends to what he has chosen to omit or add or transform. The film takes up the

action of the novel only as Aschenbach is approaching Venice. After that the significant omissions are few, but like the initial

cut they provide insight into Visconti's choice of structure and the mood which is sustained throughout the film.

The screen slowly lightens as the titles end, and we realise that we have risen to the surface of a rippling sea. Smoke

from the Esmeralda carries across the pale sky. It could be dusk, but we soon discover it is morning. Aschenbach is seated

on a portside deck, wrapped against the chill, glancing at a book of poems, dozing fitfully, taking little interest in the

views from the ship, the mud-flats, the panorama of the city, the bersaglieri drilling in the public gardens, the domes of

the Ste. Maria della Salute at the mouth of the Grand Canal (a church, incidentally, built by vow of the senate during a plague)

and he rouses himself only after the health department launch has come alongside.

He seems nervous, a little morbid, but beyond that we have no knowledge of his motivation for the trip nor of his expectations.

Without warning, as he is about to disembark, he is accosted by a debauched old man with dyed red hair, rouged lips and a

pasty face who mocks him in greeting and farewell, slurring his words almost unintelligibly and punctuating his remarks with

sinister laughter: "Au revoir, excusez, et bonjour, your Excellency! ... And by the way, sir ... "(moistening his

fingers obscenely at his lips) "..our compliments to your leetle sweet to your preetie leetle sweetheart." It

is the first of several similar affronts.

At the end of the film, Aschenbach, bearing a shocking resemblance to this tormentor, has confirmed the old man's insinuations

and dies slumped in a deck-chair as the boy Tadzio beckons him to the sea. Meanwhile the Adagietto from Mahler's Fifth Symphony,

which led us into the film and which is associated throughout with the measured approach of death, plays out to the end. It

is within this classical form of sea, city, music and the masks of death that the action of the film is contained.

Metaphoric structure takes precedence over action. Visconti has tightened that structure by selecting encounters which

reproduce the light pieces that Mann provides, but he de-emphasises other elements which would disrupt the mood. Mann's original

setting in Munich has been left out, including Aschenbach's encounter with the pug-nosed, red-haired foreigner on the steps

of the Funeral Hall, his sudden desire to travel, the vision of the crouching tiger in the jungle, all mention of his coldly

passionate service to his art, and any details of his biography. The effect of this is to contain the landscape and the mythical

dimension of the action: flashbacks relate to other times and places, but they refer to Aschenbach's preoccupation during

his term in Venice and introduce biographical information only within the chronology of his death in this city that echoes

the name of the goddess of desire.

Within that form are the elements of dissolution. Mann's exposure of the plague and its corruptions is more radical than

Visconti's, and in his description of the bacchantes with their blinding, deafening lewdness he unleashes forces which would

shatter the mood of the film as surely as they crush and annihilate the substance of the man who dreams them. Mann restates

with emphasis; Visconti reinforces with restraint.

For example, when Aschenbach first eats strawberries on the beach, Mann remarks on the warmth of the weather and describes

the delicious numbing of the senses that Aschenbach experiences. Much later, when the city is gripped with Asiatic cholera,

Aschenbach heedlessly buys soft, overripe berries to relieve the dreadful thirst he developed when he pursued Tadzio through

the filthy streets. In the film, Bogarde fastidiously bites twice into a strawberry just before we overhear a gentleman close

by warn his companions that it is very dangerous to eat uncooked fruit or vegetables in this weather. Shortly after this Tadzio

teases the governess by dancing out of her reach around the seller of strawberries and stealing one of the fruits from his

tray. She chases after him, trips and falls face down in the sand to squeaks of laughter.

The costumes, sets, and cinematography are sublime and beyond words. The film has a unique, engrossing, almost clinically

detached style. The depressive lead is simply put on camera, without the usual manipulative attempts by the director to make

us feel one way or another about him. The viewer shares what he sees, and to no less extent what he feels.

Undoubtedly the alluringly finest aspect of the film is Dirk Bogarde's performance as Auschenbach. I am not aware of a

more powerful portrayal of a dying man in all of cinema. In the hallway scene when he resolves to speak to Tadzio then changes

his mind after much mental anguish - he is fantastic. In the final scene when he actually dies he is without peer.

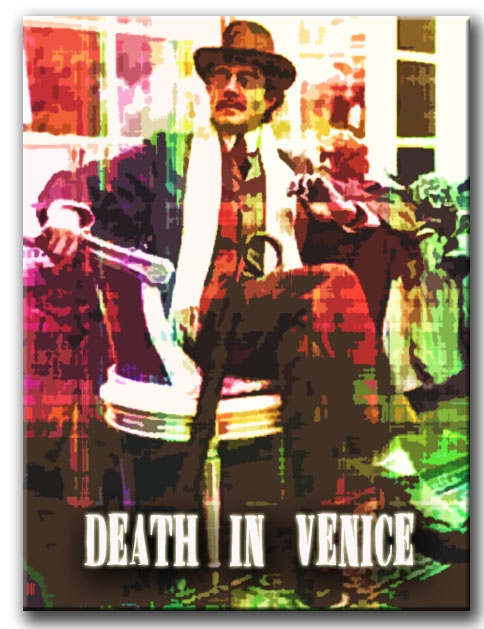

Luchino Visconti's "Death In Venice" starring Dirk Bogarde is an enthralling, richly rewarding, intellectually

and emotionally stimulating experience that elevates cinema into an indisputable art form.

|